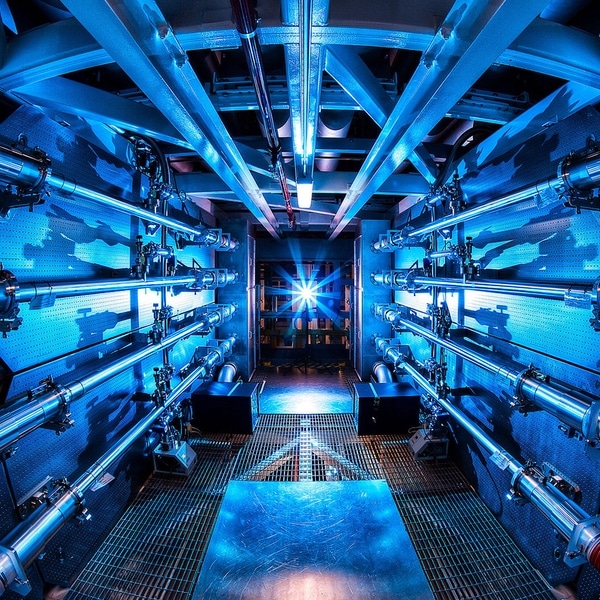

Left: Chief Sitting Bull (Photo: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution); Right: Sitting Bull's great-grandson Ernie LaPointe (Photo: Ernie LaPointe)

Our DNA determines our entire biological makeup, and it can tell us quite a lot about ourselves. For South Dakota native Ernie Lapointe, it only confirmed something he already knew. Thanks to a new advancement in methods of analyzing DNA, the Native American author was able to confirm his descendance from the famed Lakota chief Sitting Bull whose spiritual vision and leadership guided his people to victory against Lt. Col. George Custer at the Battle of the Little Bighorn (known as the Battle of the Greasy Grass to the Lakota) in 1876. More than a century after Sitting Bull’s death in 1890, 73-year-old LaPointe is now scientifically proven to be the renowned leader’s great-grandson and his closest living descendant.

These findings are all thanks to a new technique that has been in development for many years. This newly discovered method of analysis searches for “autosomal DNA” in the genetic makeup of the fragments taken from a sample. One half of autosomal DNA is inherited from the father and the other half from the mother, which means that ancestry can be tested regardless of which side of the family the ancestor belongs to. Traditional techniques look for a genetic match from DNA found in the Y chromosome, which is passed down through the male line. On the other hand, if the deceased relative was female, they look for DNA in the mitochondria that is passed from mother to child. However, neither method is very reliable, and much less so when using very old DNA.

In contrast, using autosomal DNA makes it possible to analyze DNA fragments that may have previously been considered too degraded to study. Published in October in the journal Science Advances, these findings were discovered by a team of scientists led by Professor Eske Willerslev from the University of Cambridge and Lundbeck Foundation GeoGenetics Centre. “In principle, you could investigate whoever you want—from outlaws like Jesse James to the Russian tsar’s family, the Romanovs. If there is access to old DNA—typically extracted from bones, hair, or teeth, they can be examined in the same way,” Willerslev explains.

Lock of hair from Sitting Bull's scalp that was DNA tested. (Photo: Eske Willerslev)

The DNA used in this study was extracted from a lock of hair taken from Sitting Bull’s scalp after the time of his death at the hands of the “Indian Police” who were acting under the authority of the U.S. government. The lock, along with the pair of wool leggings he was wearing, was taken by an Army Doctor at Fort Yates in North Dakota before they were obtained by the National Museum of Natural History in 1896. The artifacts were repatriated to LaPointe and his family back in 2007. Though the strands were in poor condition after years of being stored at room temperature in the Museum’s collection, the researchers were finally able to extract enough usable DNA fragments from the sample after 14 years.

“Sitting Bull has always been my hero, ever since I was a boy,” Willerslev recounts. “I admire his courage and his drive. That’s why I almost choked on my coffee when I read in a magazine in 2007 that the Smithsonian Museum had decided to return Sitting Bull’s hair to Ernie LaPointe and his three sisters, in accordance with new U.S. legislation on the repatriation of museum objects. I wrote to Lapointe and explained that I specialized in the analysis of ancient DNA and that I was an admirer of Sitting Bull, and I would consider it a great honor if I could be allowed to compare the DNA of Ernie and his sisters with the DNA of the Native American leader’s hair when it was returned to them.”

LaPointe’s claim to descendance from Sitting Bull was substantiated previously based upon oral history and tribal genealogical records. But this new scientific evidence now serves to strengthen his family’s claim even further. As the Lakota Chief’s closest living descendent, he has the legal right to reinter his great-grandfather’s remains—which may be located at one or both of Sitting Bull’s two official burial sites located in North and South Dakota. LaPointe has been in an ongoing struggle to move the remains to a location he feels has much more cultural relevance for his ancestor.

“I feel the DNA results can identify the remains buried at the Mobridge, South Dakota site as my ancestor,” says LaPointe. “This DNA research is another way of identifying my lineal relationship to my great-grandfather. People have been questioning our relationship to our ancestor as long as I can remember.”

A new method of DNA testing used a lock of hair to confirm the identity of Lakota Chief Sitting Bull's closest living descendant, his great-grandson Ernie Lapointe.

Photograph of Sitting Bull by David F. Barry, c. 1883 (Photo: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

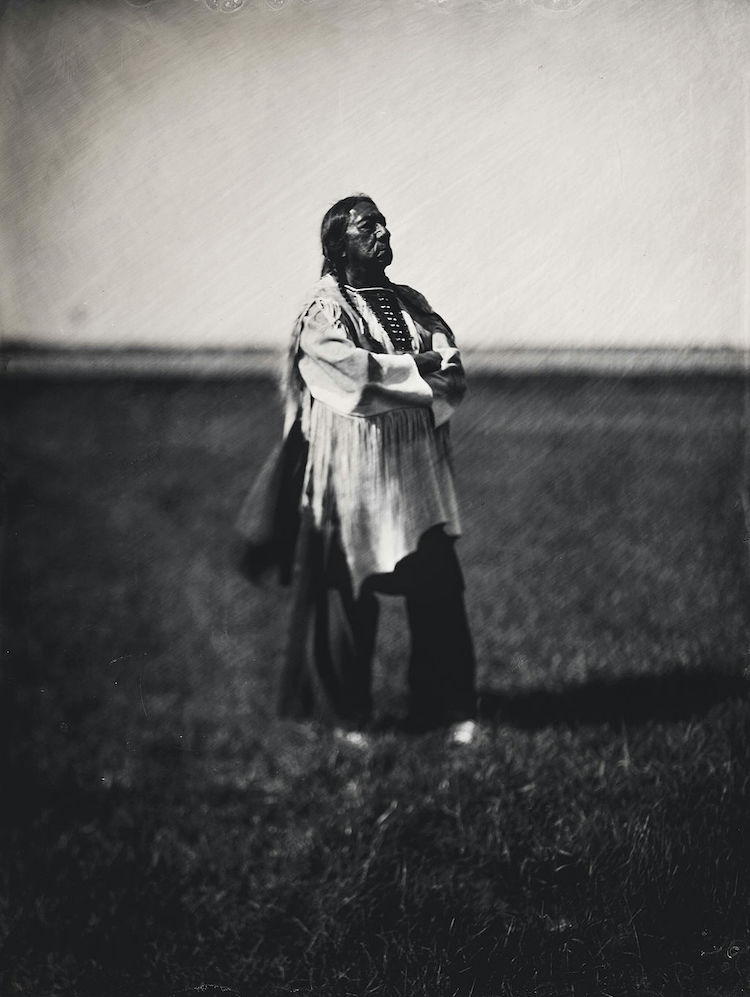

“Eternal Field,” a wet plate collodion photograph of Sitting Bull's great-grandson Ernie LaPointe, 2014. (Photo: Shane Balkowitsch, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

h/t: [NBC News]

Related Articles:

Researchers Use DNA to Reconstruct the Faces of Three Ancient Egyptian Mummies

DNA Researchers Discover 14 Living Relatives of Leonard da Vinci

World’s Oldest DNA Is Discovered in a 1.2-Million-Year-Old Mammoth

Scientists Analyze Ancient DNA to Solve Mystery of Who Built Stonehenge