“The Artist's Studio,” a daguerreotype produced by the inventor of the photographic process, Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, from 1837. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Photography has a long and innovative history, dating back to the 4th century BCE when Greek mathematicians began making pinhole cameras. During the 11th century, an Iraqi scientist developed the camera obscura, allowing images to be projected onto another surface. It wasn’t until around 1827, however, that the world’s first developed photograph was taken by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce through a process called heliography (meaning “sun drawing”).

Capturing the view from an upstairs window at his estate in Burgundy, Niépce was the first person to use light to expose an image. His heliograph method involved using a portable camera obscura next to a window to expose a pewter plate coated with bitumen to sunlight. Niépce's success led to a number of other photography experiments, including the daguerreotype technique.

Niépce began collaborating with French artist and chemist Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre to develop new ideas. After Niépce’s death in 1833, Daguerre continued their work on his own, using Niépce’s early experiments as the foundation. He developed a breakthrough technique he called the daguerreotype (named after himself). He later presented it at the French Academy of Sciences and the Académie des Beaux-Arts—an event later described as “the birth of photography.”

Read on to learn more about the development of the daguerreotype and how it's still being used today.

What is a daguerreotype?

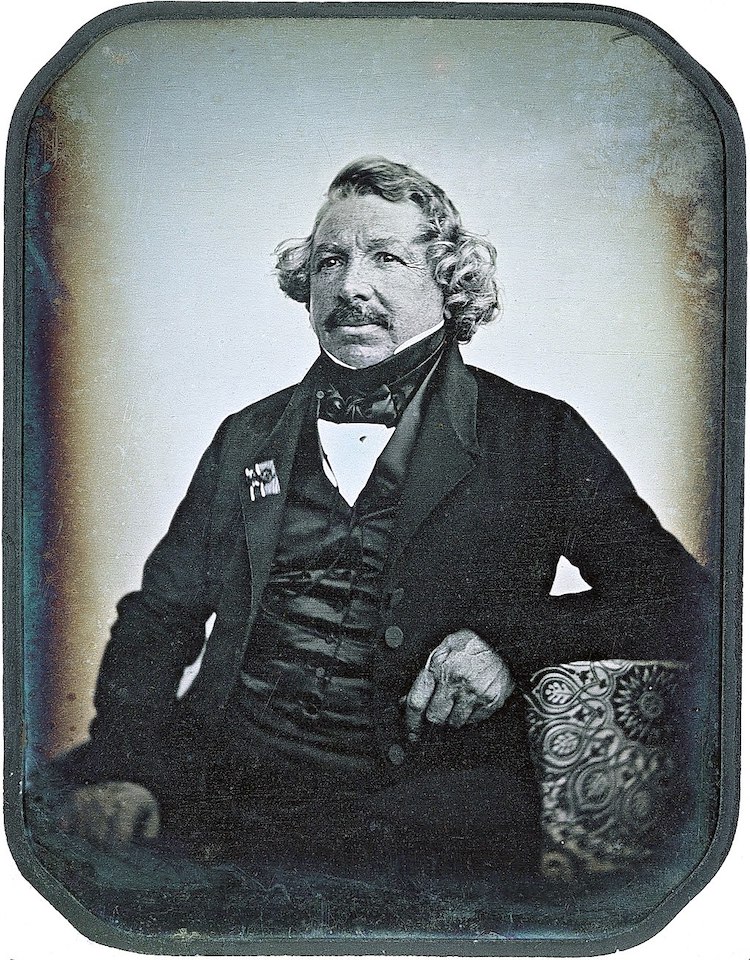

A daguerreotype portrait of Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, 1844 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Introduced worldwide in 1839, the daguerreotype was the first commercially successful photographic process. Its inventor, Daguerre, discovered a way to fix photographic images onto copper plates coated with silver iodide using a hot saturated solution of salt.

In contrast to the photographic paper we know today, daguerreotypes are heavy and inflexible. Despite the metal material, daguerreotypes are actually very fragile and were often displayed inside protective casings.

When daguerreotype studios began opening in 1840, many people wanted to have their portraits taken. However, the process was very expensive and only the wealthy could afford it. The aristocratic society of Europe and the U.S. were common subjects of daguerreotypes, but the technique was also used to capture still lifes, nature, and social events. The process continued to be widely used during the middle of the 19th century until it was almost completely replaced with new, less expensive techniques including tintype or ambrotype.

A daguerreotype portrait of Leverett Saltonstall, Jr., Charles Dabney, Jr., and unidentified companion, circa 1850. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

The Cameras

Susse Frères Daguerreotype camera from 1839. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

The earliest daguerreotype cameras were made by opticians, craftspeople, and sometimes the photographers themselves. The most popular included a sliding-box design with a lens in the front. A second, smaller box, slid into the back of the larger box, and the focus was controlled by moving the rear box back and forth. A reversed image would be obtained unless the camera was fitted with a mirror or prism to correct it.

The Daguerreotype Process

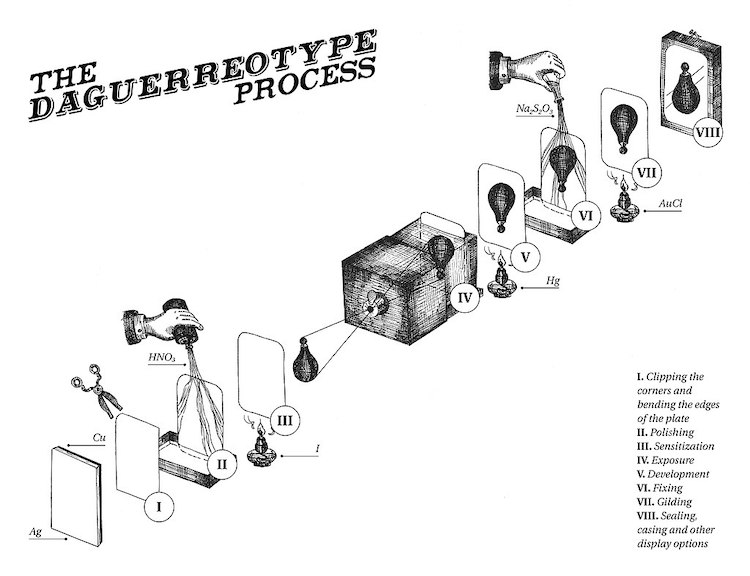

The daguerreotype development process. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, (CC BY-SA 4.0))

Polishing

In order to get the best possible result, the metal plates had to be completely free of dirt, dust, and other tarnish. The daguerreotypist often used a buff covered with hide or velvet to manually polish the silver to a near-perfect mirror finish. They also used rottenstone, then jeweler's rouge, then lampblack, and finally the surface was swabbed with nitric acid to burn off any residual organic matter. Eventually, a buffing machine was designed to assist the meticulous process.

Sensitization

The silver surface was typically exposed to halogen fumes in a dark room. When the process was first invented, only salt fumes (from iodine crystals at room temperature) were used, producing a surface coating of silver iodide. However, it was soon discovered that subsequent exposure to bromine fumes greatly increased the quality of the image. Exposure to chlorine fumes—or a combination of bromine and chlorine fumes—was also used, and a final refuming of iodine was common.

Exposure

The metal plate was then placed in the camera inside a light-tight holder with fold-out doors. The daguerreotypist then exposed the image by allowing light to enter through the holder’s doors and removing the cap from the camera lens. Depending on the chemistry used, the lighting, and the quality of the lens, the exposure time ranged from seconds to a few minutes. Once the daguerreotypist guessed the exposure is complete, they capped the camera lens and closed the plate holder doors so that no more light can get in.

Development

The plate was then put inside a special developing box, which exposes it to the fumes of heated mercury. After several minutes, the plate is removed and the image should be developed. This was a dangerous process since mercury is highly toxic. However, daguerreotypists of the 19th century rarely took safety precautions.

Fixing

To fix the image, the metal plate was immersed in a solution of sodium thiosulfate or salt and then toned with gold chloride.

Who is using the daguerreotype process today?

Ichiki Shirō's 1857 daguerreotype of Shimazu Nariakira, the earliest surviving Japanese photograph. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Although many photographers turned to newer types of photography techniques, a few devotees stuck with the daguerreotype. Those who fell in love with the signature aesthetic of the 19th-century technique continued to produce images on metal plates, and the daguerreotype process is still practiced 180 years later.

Jerry Spagnoli

View this post on Instagram

American photographer Jerry Spagnoli is perhaps the most famous modern daguerreotypist. He began exploring the possibilities of the technique in San Francisco in 1994 when he studied the technical aspects of the process and worked with 19th-century materials.

In 1995, Spagnoli began working on an ongoing series titled The Last Great Daguerreian Survey of the 20th Century in 1995, and he continued the series upon returning to New York in 1998. This project captured cityscapes and historically significant events, but Spagnoli later went on to photograph portraits and other subjects using the same technique. His abstract Glasses series depicts jumbles of drinking glasses, precariously balanced and beautifully lit.

Spagnoli says of the daguerreotype medium, “I've come to appreciate [it] as a presentation method, not simply as an image-generating system. A daguerreotype captured from any source, if properly executed, still presents the image to the viewer with uncanny immediacy.”

Adam Fuss

View this post on Instagram

British photographer Adam Fuss used the daguerreotype technique to achieve ghostly images that capture themes of fear, desire, and hope. In his image of a snake on a bed, Fuss uses the skin-shedding reptile to represent the continuous renewal of life.

“I don't see the 19th-century processes as 19th century, I see them more as historically neutral as their use in the 19th century was based on commercial issues,” Fuss said of the daguerreotype technique. “If you remove that aspect they are just really processes and are really interesting for their print and artistic possibilities.”

Chuck Close

View this post on Instagram

Patrick Bailly-Maître-Grand

View this post on Instagram

Since the 1980s, French photographer Patrick Bailly-Maître-Grand has been experimenting with old photography techniques to create striking, poetic images. When commenting on his favorite techniques, including the daguerreotype and the chronophotograph, he said, “This laborious handiwork should be seen as a nostalgic quest for the early years of photography, when all was yet to be discovered, with a box, a piece of glass, chemistry and chance.”

Related Articles:

18 Famous First Photographs in History: From the Oldest Photo Ever to the World’s First Instagram

How the Development of the Camera Changed Our World

Tintype Photography: The Vintage Photo Technique That’s Making a Comeback

B&W Victorian Era Portraits Are Brought Back to Life with Vibrant Colors