(Photo: Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration)

In a historic event, an international team of scientists and astronomers released the first ever photograph of a black hole. To take the image that many thought was impossible, they needed the help of a virtual telescope the size of Earth. The groundbreaking photograph shows a massive black hole at the center of the Messier 87 galaxy, which is located 55 million light years from Earth and was released by Event Horizon Telescope (EHT).

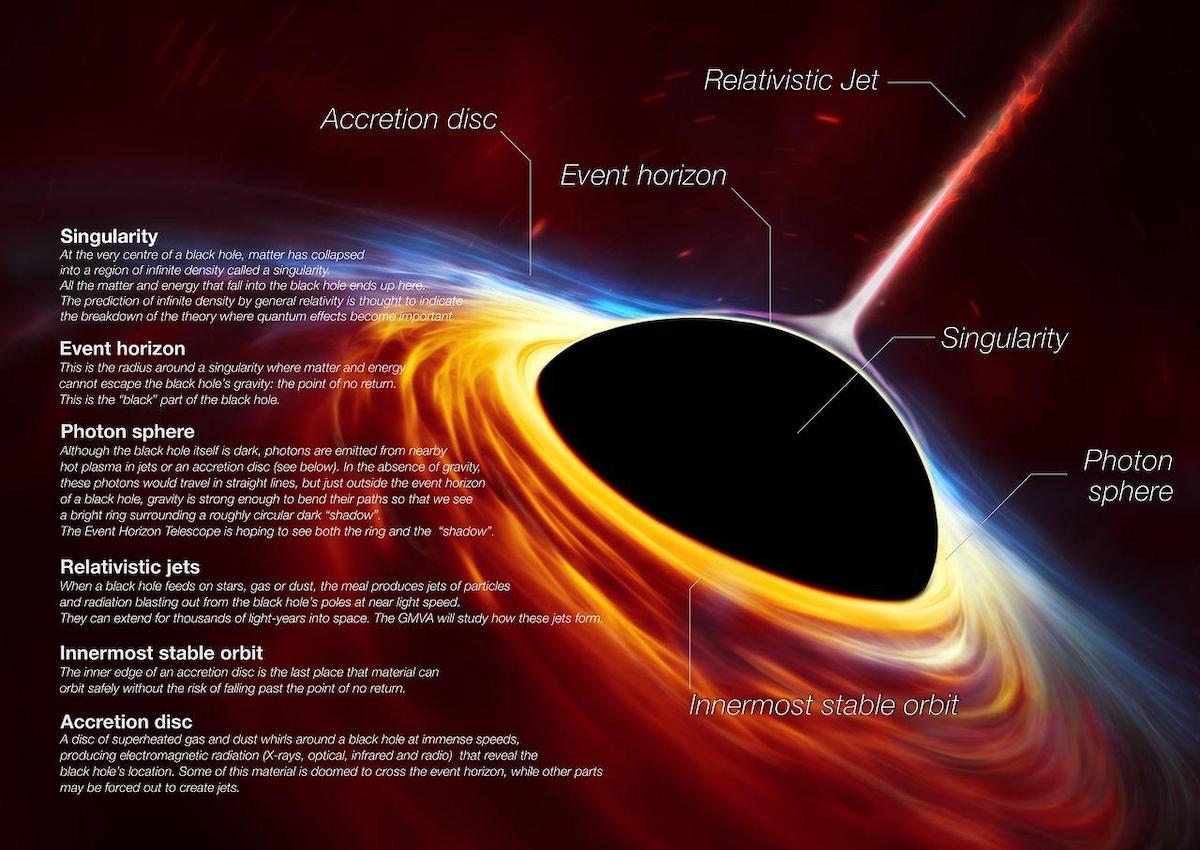

Black holes are points in space where there is so much gravity that not even light can escape. They are extremely dense due to the incredible amount of matter that is unable to leave the hole, but calling them “black” is a bit of a misnomer. “In kind of a paradox of nature, black holes, which do not allow light to escape, are some of the brightest objects in the universe,” says Shep Doeleman, a senior research fellow with the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and the director of the EHT project.

As it would have been impossible to construct a physical telescope capable of taking the photograph, EHT used technology to link telescopes around the world. This created a virtual telescope that was able to hone in on the black hole. What we're looking at in the picture is actually the shadow of the black hole, which is cast from the event horizon. This boundary of the black hole is visible thanks to the light emissions of the extremely hot gas that is compressed within the hole.

“If immersed in a bright region, like a disc of glowing gas, we expect a black hole to create a dark region similar to a shadow—something predicted by Einstein’s general relativity that we’ve never seen before,” shares chair of the EHT Science Council Heino Falcke of Radboud University, the Netherlands. “This shadow, caused by the gravitational bending and capture of light by the event horizon, reveals a lot about the nature of these fascinating objects and allowed us to measure the enormous mass of M87’s black hole.”

Artist's rendering of a black hole. (Photo: ESO, ESA/Hubble, M. Kornmesser/N. Bartmann)

Messier 87's black hole is so large that it's difficult to comprehend the scale. For one, it's 3 million times the size of Earth—larger than our entire Solar System—and has a mass 6.5 billion times more than the sun. Attempting to photograph something of that size required a carefully coordinated effort. Eight observatories and over 60 scientific institutions from 20 countries participated in the effort.

Once the different telescopes recorded their data, the information was flown to the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy and MIT Haystack Observatory so that special supercomputers could combine them. The information was then rendered into an image using an algorithm created by 29-year-old computer scientist, Dr. Kate Bouman.

Dr. Bouman, who is receiving international praise for her work, began creating algorithms three years ago as a Ph.D. student at MIT. Now an assistant professor of computing and mathematical sciences at the California Institute of Technology, she led the team who rendered the image and posted a joyous photo on Facebook of the moment she saw the photograph.

Dr. Bouman insists it was a team effort, saying, “We're a melting pot of astronomers, physicists, mathematicians and engineers, and that's what it took to achieve something once thought impossible.” But many are pointing to her work as an example of female excellence in STEM fields. MIT's Computer Science & Artificial Intelligence Lab even tweeted a photo of Dr. Bouman next to an image of Margaret Hamilton, an MIT computer scientist whose work helped ensure Apollo 11 landed on the moon.

Left: MIT computer scientist Katie Bouman w/stacks of hard drives of black hole image data.

Right: MIT computer scientist Margaret Hamilton w/the code she wrote that helped put a man on the moon.

(image credit @floragraham)#EHTblackhole #BlackHoleDay #BlackHole pic.twitter.com/Iv5PIc8IYd

— MIT CSAIL (@MIT_CSAIL) April 10, 2019

There's no doubt that all the scientists involved will be remembered for their important contributions to our knowledge of outer space. To celebrate the history-making event, six papers on the topic were published in a special edition of the Astrophysical Journal. This incredible achievement by mankind proves that theories laid out by physicists hundreds of years ago are, in fact, true. As Michael Kramer of the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy stated: “History books will be divided into the time before the image and after the image.”